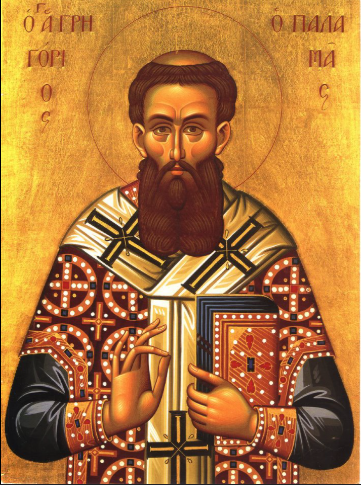

The doctrine of a real ad intra distinction between God's essence (ousia) and His energies (energeia) is the linchpin of the entire Eastern Orthodox system. It is the foundation for their asceticism, liturgy, understanding of the sacraments, and of salvation itself. Along with the filioque, it is perhaps the chief point of disputation between the West (the Reformation and medieval Roman Catholicism) and the churches of the East (especially in Greece and Russia today, and many other parts of eastern Europe). It is also a part of Eastern dogma since Palamas' official canonization in the Synod of Constantinple (1368). This doctrine has received more attention in online apologetics and polemics with the rise of figures such as Jay Dyer, Ubi Petrus, Perry Robinson (who I have had the privilege to correspond with via email a few times), Deacon Ananias, and many other defenders of Eastern Orthodoxy.

Most of the Western responses to the essence-energies distinction come from Roman Catholic thinkers, with not much attention given to it within Protestantism (aside from a short video by Gavin Ortlund, which did not engage with primary sources as much as I'd personally hope for). I hope to provide such an engagement and critique in this article, relying on Palamas' own writings, some of the work neo-Palamites shortly after Gregory's death in 1357. The colossal work of Dr. Tikhon Pino has also proven a great help to me in understanding the Eastern doctrine of God.

I will begin with working through some of Palamas’ primary writings: particularly the Triads, Dialogue between an Orthodox and a Barlaamite, the One Hundred and Fifty Chapters, and his correspondence with Gregory Akindynos. I will also take the statements of the Palamite synods in Constantinople (1341 and 1351 respectively) as being a standard representation of Eastern theology concerning the nature of deification, participation in God through His “uncreated energies”, and the nature of the Old Testament theophanies and the glory of Christ on Mount Thabor.

In his Triads, Gregory Palamas begins his defense of the Byzantine hesychasts. His first discussion unravels his view of the relationship between philosophy (particularly that of the Greek Neo-Platonists, whose views he mentions in Triads, 1.18) and man’s knowledge of God. Palamas takes issue with the entire method of the anti-Hesychasts, noting their extreme obsession with natural philosophy, it being one of the grounds which has led them to their “erroneous” notions of God.

“By examining the nature of sensible things, these people have arrived at a certain concept of God, but not at a conception truly worthy of Him and appropriate to His blessed nature.” (Gregory Palamas, Triads, 1.18)

This is not to say that Palamas condemns all philosophy simpliciter. He brings forth the analogy of a physician/apothecary who uses the flesh of a serpent to make medicine, separating the good from the bad. “But if one says that philosophy, insofar as it is natural, is a gift of God, then one says true, without contradiction, and without incurring the accusation that falls on those who abuse philosophy and pervert it to an unnatural end.” (Triads, 1.19). It is a gift of nature, not of divine grace. Palamas’ approach is in sharp contrast to that of Barlaam, who believed that even the pagan philosophers received “divine illumination.”

The chief concern of Palamas is to preserve the unknowable nature of God while also affirming man’s participation in Him. Thus the glory of Christ during the Transfiguration on Mount Thabor became his chief impetus for defending a distinction between the divine essence and energies. Since the glory of Christ was accessible to the human senses of the disciples, it could not have been the divine essence. However, the divine essence and energies are not two separate “things”, but two modes in which God is wholly present (Norman Russell, Gregory Palamas: The Hesychast Controversy and the Debate with Islam, pg. 23).

It is worth noting in passing that the statement that “we know God by His operations, and do not know His very essence” is uncontroversial, and agreed upon by the Western churches as well. For example, Aquinas himself wrote “We cannot know him naturally except by reaching him from his effects [energies], it follows that the terms by which we denote his perfection must be diverse, as also are the perfections which we find in things. If, however, we were able to understand his very essence as it is, and to give him a proper name, we should express him by one name only. And this is promised to those who will see him in his essence." (Summa Contra Gentiles, I.31). This observation is not limited to the medieval scholastics. John Calvin said that “Indeed, his essence is incomprehensible; hence his divineness far escapes all human perception. But upon his individual works he has engraved unmistakable marks of his glory, so clear and so prominent that even unlettered and stupid folk cannot plead the excuse of ignorance.” (Institutes, 1.5.1)

Grace (charis) is both created and uncreated. In his Letter to Athanasios of Kyzikos, Palamas discuss different senses in which the word “grace” might be used, referring both to the giving of the gift by the Holy Spirit and man’s reception thereunto. Thus, we see a fundamental Palamite distinction between the gift as the act of giving and the gift as something received. The former is uncreated, while the latter is obviously created. “Sometimes being deified is called deification, and sometimes that whereby the object of deification is deified, by receiving it, is called deification.” (Against Gregoras, 3.21)

In his second Triad, Palamas begins to bring forth a distinction between essence and energies, albeit not using that exact terminology as of yet.

“But you who introduced the methods of definition, analysis, and distinction, come to know, and deem us the ignorant worthy to teach. For [the light] is not the essence of God, for the latter is both inaccessible and imparticipable. It is not an angel, for it bears the marks of the Master, and sometimes it goes out from the body—or it is not borne up to the unspoken heights without a body—and at other times it transforms the body and gives it a share of its own proper splendor . . . In this way, therefore, it also deifies the body, becoming visible—O the miracle—to bodily eyes.” (Gregory Palamas, Triads, 2.3.8)

Peter Totleben contends that Palamas’ early framing of the distinction in terms of the divine essence and the “uncreated light” tends to lean more into a real distinction, with his defense of hesychast mysticism lurking closely in the background. However, the framing of the distinction with the categories of essence and energies belong more to the realm of speculative philosophy (The Palamite Controversy: A Thomistic Analysis, pg. 32n63)

In the second Triad, Palamas clarifies multiple times that he is not teaching mere apophaticism simpliciter:

“Thus the perfect contemplation of God and divine things is not simply an abstraction; but beyond this abstraction, there is a participation in divine things, a gift and a possession rather than just a process of negation….If one speaks of them, one must have recourse to images and analogies—not because that is the way in which these things are seen, but because one cannot adumbrate what one has seen in any other way.” (Gregory Palamas, Triads, 1.3.18)

This contemplation of God’s energies is not done through the intellect or senses simply. Rather, it consists in mystical experience: “Following the great Dionysius, one should perhaps call it union, not knowledge.” (Gregory Palamas, Triads, 2.3.20). During this contemplation, one does not directly know through what medium he sees the divine energies. Palamas cites the Apostle Paul: “whether in the body, or out of the body, I cannot tell: God knoweth.” (2 Corinthians 12:2-3)

In terms of the divine names, they do not properly describe God. Even the term “essence” is only improperly given to God, since He is ύπερόυσια:

“It is therefore not lawful, for anyone acquainted with the truth beyond all truth, even to name it ‘essence’ or ‘nature’ when naming it in the proper sense. Since, again, it is the cause of all things, and all things are around it and for it—and since it is itself before all things, having conceived them all in itself in a simple and uncircumscribed manner—it is named from all of them catachrestically, but not properly.” (Gregory Palamas, Theophanes, 17)

Therefore, when “the essence is known from the energy” this only pertains to “the fact that it is, not what it is….The essence is what is known through the energy as to the fact of its existence.” (One Hundred and Fifty Chapters, 141). To me, it seems that Palamas’ system completely renders it impossible for us to have any knowledge of what God is (quid est). You can see here that Palamas also posits some sort of distinction between essence and existence in God, claiming that a real identity between them would make a statement like “God exists” redundant (e.g., ‘existence has existence’). Being (το όν) is itself one of the divine energies, according to Palamism, since God in Himself is υπερούσιος. This misunderstanding is based on a conflation of material and formal identity. A simple study of Aquinas on the divine relations or of Scotus of the formal distinction would erase this difficulty quite easily.

In fact, Palamas even says that there is no difference of signification between the divine names we ascribe to God based on the energies.

“The divine essence, then, is altogether nameless, since it is also inconceivable. But it is named from all its inherent energies—none of the names there differing from one another in signification. For from each one of all the things said of God nothing else is denominated but that Hiddenness, which is in no way known as to what it is.” (Gregory Palamas, Against Gregoras, 4.48)

When it comes to defining what exactly are the divine “energies”, Palamas’ most important point of reference is the light of Christ on Mount Thabor, witnessed by the disciples during the Transfiguration. While Barlaam posited it as a created effect, Palamas firmly denied this, saying instead that it was “the effulgence, glory, and radiance of his nature, proceeding from him by nature.” (Against Gregoras, 4.40)

Q: Do the energies inhere in God, according to Palamism?

A: “Even the things said apophatically of God inhere (πρόεστι) in God naturally and are not nature, according to the divine Cyril [of Alexandria].” (Contra Akindynos, 4.11.25). Elsewhere, Palamas identifies these negations (timelessness, uncreatedness, etc.) with “the things around the essence (περι την ουσιαν).” Tikhon Pino describes Palamas’ view as being that there are “‘all things said of God cataphatically and apophatically’ are not essence but attributes inhering in the divine nature.” (Essence and Energies: Being and Naming God in St. Gregory Palamas, pg. 57). He explicitly describes the energies at one point as “those things that inhere in God by nature.” (Contra Akindynos, 4.7.13)

Palamism is unequivocally clear in its denial of the pure actuality of God. This is why Gregory refers to the energies/dynamis as “nothing other than a readiness to act.” (Gregory Palamas, Letter to Daniel of Ainos, 21). The energies of creation and providence and rendered as simply God’s ability to perform these respective acts whenever he so chooses (Tikhon Pino, Essence and Energies: Being and Naming God in St. Gregory Palamas [New York: Routledge Press, 2023], pg. 62).

“it is not acting and energy but being acted upon and passivity which causes composition.” (The One Hundred and Fifty Chapters, 145)

Palamas distinguishes between an energy and its ad extra effect (αποτελεσμα). These “created signs” are actualized (ένεργηθεντα) by the energy, and therefore distinct (Contra Akindynos, 1.4.9). Not every spiritual gift bestowed by the Holy Spirit is to be identified with the uncreated energies per se (Tikhon Pino, Essence and Energies, pg. 87). For example, the miracle of Christ walking on water in itself is a created phenomenon, but the divine grace and power through which that miracle is performed is the uncreated energies (Gregory Palamas, Against Gregoras, 4.30).

Most interestingly, we sometimes find Palamas speaking of the “beginning” and “end” to the energies. “Palamas is insistent that it is the acts themselves—creation, providence, foreknowledge—that come to be or pass away (or both), not merely their effects.” (David Bradshaw, Aristotle East and West, pg. 262). This is, of course, in continuity with 20th-century Eastern theology: “God himself changes for our sake in his operations, remaining simple as the source of these operations and being wholly present in each one of them.” (Dumitru Staniloae, The Experience of God [Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1994], pg. 126)

Elsewhere, Palamas distinguishes between the energies and their temporal manifestation, ascribing a temporal beginning and end only to the latter:

“The essence of the Spirit is completely hidden, while the energy of the divine Spirit, manifested through its effects, begins and ceases at the level of manifestation, without the creatures, as we have said, attaining to eternality….But the energy of God does not, for this reason, begin and cease unqualifiedly. For God, who is always active, has an unceasing energy, ever seeing all things and providing for all things. For my Father until now is working, and I am working [John 5:17].” (Gregory Palamas, Contra Akindynos, 6.21.78)

“What is manifested from the acting is not the essence of the one acting, but his power and energy, which was in him even before the manifestation.” (Letter to Damianos, sect. 16)

This distinction made by Palamas should give great caution to Eastern Orthodox apologists who wish to insist that Thomistic divine simplicity leads to the necessity of creation. Might their argument just as easily be leveled against Palamas when he distinguishes the uncreated energy from its manifestation in time? Is creation an uncreated energy of God? If it is simply that God has a power to create which is only acted out in the beginning of the world, then this seems to lead to a passive potency being in God. “For even if there has been no beginning and end of the creative power, still, there has been a beginning and end of its activity, that is, the energy at the level of what has been created.” (Triads, 3.2.8). Perhaps this is why there are a few occasions in which Palamas differentiates between dynamis and energeia: “Power advances into energy, and from the energy the creature comes to be.” (Triads, 3.2.19). In fact, Palamas even is willing to speak of actualization in God ad intra, by using the analogy of the “inner” and “outer” word, the former being the movement of the rational intellect, the latter being an external vocalization (Contra Akindynos, 5.13.55).

The energies are also often described as the “things around God.” (ta peri Theou), including both affirmations and negations. Under this label include things like immutability, incorporeality, and invisibility (Against Gregoras, 2.7). This would also be an accurate label for the light of Christ at Mount Thabor (Triads, 3.1.20).

When it comes to discussing the nature of the essence-energies distinction, the concept of “antimony” comes into the light. It may also be aptly termed the “coincidence of opposites.” Throughout Palamite literature, we see an attitude of comfort and complacency in affirming seemingly blatant contradictory statements about God, as for example that He is both seen and unseen, participated and unparticipated.

“The divine nature must be said to be at the same time both exclusive of and in some sense open to participation. We attain to participation in the divine nature, and yet at the same time it remains totally inaccessible. We need to affirm both at the same time and to preserve the antinomy as a criterion of right devotion.” (Gregory Palamas, Theophanes, in PG 150:932D)

“[Anti-Palamites] base themselves upon a rational, philosophical notion of divine simplicity, and fail to allow properly for the fact that in God the opposites coincide; he transcends our man-made conceptions of unity and multiplicity, which cannot be applied to him without qualification.” (Kallistos Ware, “The Debate about Palamism,” Eastern Churches Review 9 [1977], pg. 51)

It is this need to affirm both unity and multiplicity in God (the classic problem in philosophy of the one and the many) that is a chief reason for the East’s insistence on a real distinction between ousia and energeia. “It is completely impossible and utterly irrational for something to be both one and many in the same sense.” (Gregory Palamas, One Hundred and Fifty Chapters, 117.11-13)

Once again conflating material and formal predication/identity, Palamas says that the difference of signification with divine names entails a real distinction between them ad intra:

“In the case of the energies, each of the names has a different signification. For who does not know that creating, ruling, judging, providing, and God’s adoption of us by his grace, differ from one another?” (Gregory Palamas, One Hundred and Fifty Chapters, 144.7-9)

It is obvious from Palamas’ own writings and from the Synodol Tomos that the East does indeed teach a real distinction between essence and energies. However, another instance of this teaching is found in the dialogue between John Kantakouzenos and the Latin legate Paul of Smyrna:

“We believe in the essence of God, as possessing the energy which proceeds from it without division. The energy does not exist as separate from the essence (οὐ διϊσταμένην) but differs from it according to the notion (διαφέρουσαν ἐπινοίᾳ) as warmth differs from fire or brightness from light….According to the teaching of the theologians and the decision of the Synod, the essence and the energy of God are, I assume, neither totally identical nor totally distinct. In actual fact, both statements are true according to a different logical criterion (οὐ μὴν τῷ αὐτῷ λόγῳ). True, an object cannot be both the same and different according to the same logical criterion (κατὰ τὸν αὐτὸν λόγον). However, the union as well as the inseparability and the indivisibility are accorded to the reality ( τῷ πράγματι), whereas the distinction (διάκρισις) is merely accorded to the notion (μόνῃ τῇ ἐπινοίᾳ).” (Ep. Cant. 3.5.15, 17, in Iohannis Cantacuzeni Refutationes duae Prochori Cydonii; et, Disputao cum Paulo Patriarcha Lano: epistulis septem tradita, ed. Edmond Voordeckers & Franz Tinnefeld, [Turnhout: Brepols; Leuven: University Press, 1987]).

“There are three realities in God (Τριών όντων του θεού), namely, substance, energy and a Trinity of divine hypostases.” (Gregory Palamas, The One Hundred and Fifty Chapters, 75.1-2)

Another facet which proves that the Palamites taught a distinctio realis is the accusation made by his opponents, particularly Barlaam and Akindynos, that Palamas’ doctrine led to some form of ditheism, in which there is a “higher” and “lower” divinity (θεότης) in God (Gregory Palamas, Contra Akindynos, 2.5.13; 6.3.6). Palamas gave further fuel to these accusations by insisting that the uncreated Light is subordinate to divine essence (how this does not introduce composition given Palamas' own criterion of passivity is quite the mystery to me!).

“The fact that there is a cause as well as something caused; participability and imparticipibility; something that characterizes and something characterized, etc. —the one transcendent and the other subordinate (ύπερκείμενον και ύποβεβηκός) - presents no obstacle to God’s being one and simple, having a single, equal, and simple divinity.” (Gregory Palamas, Third Letter to Akindynos, 3.7)

“The things contemplated essentially around God are many and yet do not in any way impinge on the profession of simplicity, all the more will this ‘symbol’ having the form of light, which is one of them, do it no harm.” (Triads, 3.1.19)

“When we call some divine power or energy of God ‘divinity,’ there are many divine energies that take this appellation. These include the energies of vision, purification, deification, and oversight, God’s being everywhere and nowhere, which is to say his being ever-moved, as well as the light that shone forth on Thabor around his elect disciples.” (Gregory Palamas, Theophanes, sect. 9)

“Just as the many Spirits do not do away with the unity, simplicity, and non-synthesis of the Spirit, since they are his energies, so, in the same way, even if someone should speak, in accordance with the saints, of many divinities, meaning the energies of the one Divinity (μιᾶς θεότητος), he does not do away with its unity, simplicity, and lack of synthesis. Beyond this, even if the name ‘divinity’ should signify many things, still none of the things signified is unsuited to the three Persons, so that even in this way there is a single divinity of the three.” (Gregory Palamas, Letter to Arsenios, sect. 4, in PS 2:317.25-318.5)

When it comes to this particular dispute, the most oft-quoted and studied passage is from the aforecited Third Letter to Akindynos (3.15), which technically has two versions which ought to be cited here in parallel format:

“There should not be any wonder for us that, in God’s case, essence and energy are in some sense one and are one God, and at the same time essence is the cause of the energies and, in virtue of its being their cause, is superior to them. For the Father and the Son, too, are one thing and one God, and yet “the Father is greater” (Joh. 14,28) than the Son in terms of His being the cause. And if there [sc. in the case of the Holy Trinity], for all the self-subsistence of the Son and for all His being co-substantial [with the Father], “the Father is” nevertheless “greater” [than the Son], all the more will the essence be superior to the energies, since these two things are neither the same nor different in substance, as these properties [sc. being of the same or of different substance] regard self-subsistent realities and no energy at all is self-subsistent.” (Gregory Palamas, On the Divine Energies and Participation in Them, §19, in Γρηγορίου τοῦ Παλαμᾶ συγγράματα. ed. Panagiotes K. Chrestou, 5 vols. [Thessaloniki: Kyromanos, 1962-1992], 2:111)

It is obvious that Palamas is saying that the distinction between the essence and energies is the same as the distinction between the divine Hypostases, both relying on a common basis, i.e. causal relations. Just as the Father is superior to the Son by virtue of being His eternal cause (αἰτία) as Begettor, so also is the transcendent essence superior to the energies by being their cause, and yet they are still one God.

Palamas seems to even be saying here that the superiority of essence over energies is even greater than that between the Father and the Son, since “these two things are neither the same nor different in substance,” since speaking of identity and distinction in substance pertains only to that which is self-subsistent, which is obviously not applicable to God’s uncreated energies.

One rather curious observation made by John Dematracopoulos is that some of Palamas’ Byzantine supporters made great use of the concept of επίνοια to soften the essence-energies distinction (“Palamas Transformed: Palamite Interpretations of the Distinction between God’s ‘Essence’ and ‘Energies’ in Late Byzantium,” in Greeks, Latins, and Intellectual History 1205-1500, ed. M. Hinterberger & Ch. Schabel [Leuven: Peeters, 2011], pgs. 281-292). I will attempt here to give a detailed outline of this phenomenon as observable in Byzantine Palamism of the mid-14th century:

[1]. “To see that essence and energy are not in every aspect one and the same thing, but are united and inseparable and yet are distinguished only conceptually, pay attention to how the saints state that these things are two and testify both to their unity and distinctiveness. … Hence we do not state that there are two deities or Gods, as they [sc. the antiPalamites] slander us; instead, what we state on the basis of what we have learnt from the saints is that this Deity, which is participated in by those who are deified, is not a proper essence or substance, but a natural power and energy present within God Himself, the Holy Trinity, absolutely inseparable and indivisible [from Him], the difference [between them] being only conceptual… The holy Fathers and Doctors, as we have already said, even if they say that God’s essence is one thing and His energy is another thing, conceive of the energy—and they write thus—as inseparable and indivisible from the essence, as proceeding from it and as having existence and being present only in this very essence, since the separation (or, better, the difference) is construed only conceptually. Thus, in the case of those things which have their existence in other things, but do not subsist or exist autonomously in themselves, one does not speak of composition, as we have said.” (Philotheos Kokkinos, Κεφαλαια της αίρεσεως Άκινδυνου και Βαρλαάμ, §4, 8-9, cited by Demetracopoulos, 283-84)

[2]. “That substance is one thing whereas hypostasis is another does not entail that substance exists in separation from hypostasis; nor does the fact that essence and energy are not the same entail that the divine energy is separated from the divine essence; on the contrary, the distinction between them is conceptual, whereas their unity is real and indivisible.” (Neilos Cabasilas, Oratio brevis de Gregorii Nysseni dicto; “Increatum nihil nisi…”, §12)

[3]. “We believe that God’s essence has energy, which emanates indivisibly from it and does not lie at a local distance from it, but just differs from it conceptually, in the manner that heat differs from fire and shine from light, to use the examples put forward by the theologians, e.g., by Cyril (of Alexandria) and Basil (of Caesarea), who have verbatim as just mentioned.” (John Kantakouzenos, First Epistle to Paul, 1.13-18)

[4]. The most succinct neo-Palamite explanation of the concept of επίνοια in relation to the essence-energies distinction comes from Theophanes of Nicaea, who applied the language of a “conceptual distinction” only to the notion of separability, while also maintaining a distinctio rationis:

“The divine essence and energy differ from each other in reality, because, as has been sufficiently shown, they are both real things; on the other hand, they are divided and separated from one another only conceptually, not really; for, according to the divine Anastasius, ‘they cannot be separated from each other’, just like the heatness in the fire cannot be separated from the fire and the sunlight from the sun. Even more, these things form a unity only partially (indeed, the sunlight is connected with the disk and its source only as far as some part of it, whereas its largest part runs through the end of the world), whereas in the case of the divine essence and energy the connection is not regarded as partial, but, since each of them is “incircumscribable”, exists in each other in its totality.” (Theophanes of Nicaea, Ἐπιστολὴ ἐν ἐπιτομῇ δηλοῦσα τίνα δόξαν ἕξει ἡ καθ’ ἡμᾶς ἐκκλησία περὶ τῶν παρὰ Παύλου προενηνεγμένων ζητήσεων, in MS. Barocci 193, ff. 86r)

I understand myself that it is quite difficult to put all of this data into one coherent critique of Palamism, and so I have chosen to conclude this article with a series of questions which I hope will pave the way further in East-West dialogue, and perhaps spark renewed interested in Eastern theology amongst the confessional Reformed folk, of whom I am a humble part.

[1]. Is simplicity itself an energy of God which is distinct from the essence? If so, then how can Palamas continue to claim any notion of simplicity whatsoever? We would then have an essence which is non-simple in itself but "is simple" through a distinct energeia. If simplicity is not distinct from the essence, then this is a case in which some attribute or perfection which is predicated of God is admitted to be really identical to His essence.

[2]. Why do later Palamites seem to soften the "realness" of the distinction between essence and energies?

[3]. Is the Palamite notion of ἐπίνοια the same as what we find in St. Basil of Caesarea (see Radde-Gallwitz and Delcogliano).

No comments:

Post a Comment